Introduction

It was a striking yet somehow vaguely familiar scene. Julius Malema, the self-styled “Commander-in-Chief” of the Economic Freedom Fighters, a radical offshoot of the ruling African National Congress, addressed a crowd of 90 000 cheering ‘redshirts’ at a party rally at a stadium in Johannesburg on Saturday 29 July 2023. The event was being held to celebrate the tenth of anniversary of the founding of the EFF in 2013.

In his speech Malema railed against Western imperialism and denounced South African President Cyril Ramaphosa as a “coward” for failing to guarantee safe passage to Russian President Vladimir Putin should he attend the upcoming BRICS summit. “We are Putin and Putin is us”, Malema told the gathering, “and we will never support imperialism against President Putin.” He also once again called for “the land” to be taken from the white minority and returned to the “hands of the rightful owners”. At the end of his speech Malema was raised up into the air on a red platform his arm stretched out towards the crowd.

After a toast to his leadership Malema returned to the microphone for an encore. He now launched into an old liberation movement chant: “Shoot to kill! Hamaza! [get a move on!]; Kill the Boer! Kill the farmer! Kill the Boer! Kill the farmer!” He then imitated the sounds of an AK47 being opened up “Brrr! Pa! Brrr! Pa!”

In South Africa “Boer” has a double meaning. It can refer to white farmer, but it is also a derogatory term black racialists use to refer to Afrikaners in particular, and white South Africans more generally. This was, in other words, a call to racial killing, made in person to an audience of tens-of-thousands of militant activists.

It was a particularly disturbing one if you happen to have at risk-family members – and particularly elderly family members - living in a South Africa. Elon Musk, who was born and raised in the country and has a father and other relatives still living there, reacted to a clip of this moment being circulated on X, by tweeting the following Monday: “They are openly pushing for genocide of white people in South Africa”, asking Ramaphosa “why do you say nothing?”

A striking silence

The German newspaper Bild recognised the newsworthiness of the story - and its potential to embarrass the Russian-sympathising Western hard-right - running its report under the headline, “Putin-Friend wants to kill white people.” The initial reaction from the American media was, by contrast, deathly silence. Although John Elligon, The New York Times’ correspondent in Johannesburg, attended the EFF rally, the newspaper initially ran no report on either it or Malema’s incendiary chant.

The negative reaction from America’s newspapers of record, when it finally arrived, was directed at Musk rather than Malema. The Washington Post was first out of the blocks accusing Musk, in its headline, “of rais[ing] the specter of ‘white genocide’”. In his analysis Ishaan Tharoor suggested that while Malema’s chant tapped into historic “black grievance” there was little need to be concerned that there could be any violent consequences flowing from it. He stated at one point in his article that there is “little new about a far-left rally featuring such a song” and, at another, that there is “no evidence of excess violence in South Africa directed toward white farmers”. The ruling ANC had even expelled Malema for singing ‘kill the boer’ in 2012, he added, “after a firestorm of controversy”.

For its part the report in the New York Times, when it finally appeared, echoed many of these same lines. “Despite the words”, the newspaper reported, “the song should not be taken as a literal call to violence, according to Mr. Malema and veterans and historians of the anti-apartheid struggle. It has been around for decades, one of many battle cries of the anti-apartheid movement that remain a defining feature of the country’s political culture.”

The article suggested that while there had been some attacks on white farmers, which people on the right in South Africa and the United States had apparently “seized upon”, the claim that there had been “mass killings” was a false one. The ANC, the newspaper claimed, had “distanced itself from the song in 2012 — the same year it expelled Mr. Malema for his incendiary statements.”

Although the New York Times has been subsequently criticised by Musk and others for hypocrisy and double standards this unequivocal dismissal of the issue certainly influences well-meaning centre ground Western opinion. If you don’t quite know who or what to believe then the best policy is generally just to avoid reporting on the controversy, as most Western publications have done.

Who wants to ‘kill the boer’?

The idea that this chant is and was never meant literally collides with certain unavoidable realities. One of these is that in the mid-1980s leaders of the then exiled-ANC broadcast repeated calls to their supporters in South Africa to rise up against the “blood-sucking” white farmers - as part of its broader call for insurrection and People’s War - and seize the “land which rightfully belongs to them”. They also approved various overt and covert operations by the ANC’s armed wing Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK) against this group. In other words, at the time these words were being chanted under apartheid it was ANC policy both to attack white farmers and incite popular violence against them.

This effort to extend its People’s War into white commercial farming areas in the 1980s was largely unsuccessful and these remained, for the most part, unaffected by political violence. In August 1990, after its unbanning and the National Party government’s final dissolution of apartheid, the ANC nominally suspended its armed struggle. However, it continued to recruit radical youth into paramilitary units in preparation – in part - for a return to insurrection should it fail to get its way in the negotiations around a future constitution for the country.

Part of the indoctrination process involved teaching such youth the struggle songs and chants of the movement, more than one of which ideated attacking “the boers”. These units were also informally instructed to use robbery to secure weapons and funding for their operations, something which contributed to the surge in attacks on policemen and farmers recorded at the time. Apla, the armed wing of the ANC’s more Africanist breakaway faction, the Pan Africanist Congress, openly targeted farmers and other white civilians in the 1991 to 1993 period. Its slogan was ‘one settler one bullet’.

Julius Malema, who was born in 1981, is a political product of this era and this ANC preparation for a return to insurrection. Growing up poor and fatherless in the township of Seshego outside Pietersburg in the northern part of the country he was recruited into one of these paramilitary units by the returning ANC as a child auxiliary and taught how to use a Makharov pistol and sing ‘shoot the boer’ as a nine-year-old.

If you read the court transcripts of the court case cited by The New York Times Malema did not always hew closely to his legal pleadings. At one point in his evidence, he told his own lawyer that as a twelve-year-old in 1993 he, along with those who shared his political convictions, were more than prepared to go out attack the historic enemy. In reference to the moment in April 1993, when the ANC and MK leader Chris Hani was assassinated by the Polish right-winger Janusz Waluś, he stated that “they” – meaning, the whites - “must thank Mandela for a very long time because when they killed Chris Hani all we waited for was a statement from the Commander in Chief President Mandela saying to us now let us go for them.” His lawyer hastily jumped in to stop him saying anything further.

Asked later to clarify by the opposing counsel what he meant by this Malema expressed regret at the path not taken in 1993, adding that “We were waiting for the leadership to just give an instruction. And all corners of South Africa we were going to engage in a revolution. And perhaps should that have happened, we would not been sitting here and entertaining racists.”

Violence on the farms post-1994

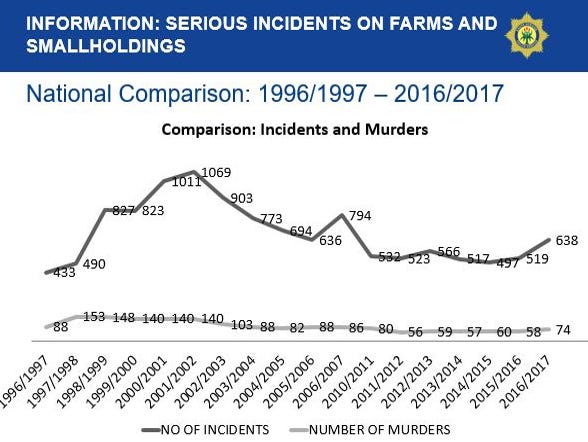

The claim that calls to kill farmers were never meant or understood literally also runs up against the reality that unnaturally high numbers of people have been killed in armed attacks on farm homesteads over the past three decades in South Africa. After the ANC was elected to office in April 1994 attacks on farmers continued unabated, even as other forms of political violence declined. In the four-year period between 1998 and 2001, when this type of violence was at its height, 577 people were murdered in 3 499 attacks on farms and small holdings, according to the police.

In 2001 there were, according to one detailed police analysis, just over a thousand attacks (1 011) on farms (630) and smallholdings (381) in which there were 392 attempts by the attackers to murder their victims, in 147 cases successfully. In 514 of these incidents the victims were first attacked inside the house and in 295 cases in its immediate vicinity. In 88 cases the farmers were ambushed elsewhere on the farm. In line with the many political pre-1994 farm attacks there was an element of robbery or plunder involved in most of these incidents. These attacks predominantly occurred in the Eastern half of the country, with farms in the provinces of Mpumalanga (234) and KwaZulu Natal (108) particularly hard hit in 2001.

In almost all ways this violence was highly anomalous. In most societies homicides are predominantly the result of inter-personal or inter-gang violence between young adult males living in urban areas. Attacks and murders of older people in their homes on farms by armed bands is a vanishingly rare form of murder in most countries, outside of insurgency situations. For whatever reason this type of murder became highly prevalent on South Africa’s farms post-1990.

Whether shadowy elements in the liberation movements continued to run covert operations against farmers after 1994, as they had done previously, remains a matter of conjecture. It is obtuse to insist, as many commentators continue to do, that this jarring violence lay in no way downstream of earlier liberation movement efforts to unleash violence against this class of “oppressor”.

The number of attacks and murders on farmers in the Eastern half of South Africa have come down significantly from the extraordinary numbers recorded in the early 2000s, but are still far above what they were before 1991. These areas can hardly be considered “safe” either, with farmers and their family members living a frontier existence where they are entirely dependent on their own efforts and organisation to secure their safety.

A magical disappearing trick

What though of the Washington Post’s claim, seemingly endorsed by the New York Times, that there is and has never been anything “excessive” about these killings? Tharoor writes that not only were farmers not at heightened risk of being attacked and killed in their homesteads but in fact “the data suggests the opposite, that they are far less likely to be the targets of violent crime than the general South African population.”

“The data” he links to is a “Monkey Cage blog” published on the Washington Post website in May 2019. It contains a striking graph purporting to show that the murder rate of farmers between 1996 and 2018 was always a small fraction of the national murder rate. There are numerous conceptual errors in the analysis[1] but the key problem with its historic estimates is this: To get to rate for the murder of farmers per 100 000 in a given year obviously requires dividing the number of farmers murdered over the population of farmers - some 43 000 people, according to the 2007 state agricultural census.

The Monkey Cage analysis gets to its estimates, however, by dividing the number of farm murders over all the 803 000 people that worked on commercial farms in 2007, including seasonal and casual labourers. It mistakenly describes them as the “full-time residents of farms”. By using this number as the denominator, it effectively undercuts the correct rate by between ten- to twentyfold.

To use a somewhat simplified example to illustrate this point: Assume that 40 000 (white) farmers employ 760 000 (black) workers - to give a total of 800 000 people working on commercial farms. In a particular year forty of those farmers are then murdered in attacks by armed gangs on their homesteads. There are forty other fatalities resulting from these attacks, meaning 80 people are killed overall. Most of these are family members of the farmers but some of the victims are workers.

That would mean a murder rate for the farmers themselves of 100 per 100 000 - if you divide the number of farmers murdered (40) over the population of farmers (40 000). This would be twice the national murder rate assuming that it was, say, 50 per 100 000, and twenty-five times the national robbery-murder rate of, say, 4 per 100 000.

However, if you divide eighty over 800 000 then you get to a murder rate of only 10 per 100 000. This is now five times lower than the national murder rate. This magical disappearing trick is, in essence, the one that the Monkey Cage performed to show that farmers “are far less likely to be the targets of violent crime than the general population” and “are, on average, safer than the South African population at large”. This analysis would be laughable were it not regarded as dispositive on the matter by so many members of America’s Ivy League educated elite.

The ANC and ‘shoot the boer’

The suggestion that the ANC did not condone Malema’s singing of ‘shoot the boer’, or even expelled him for it, is also a misrepresentation of well-established facts. After the controversy over Malema’s singing of the song first broke in March 2010 the ANC publicly defended it. The court case by AfriForum, an Afrikaner civil rights organisation, to have the words “shoot the boer” declared hate speech was widely criticised in the media as a provocation against the ANC, and it was regarded by the movement itself as an unjustifiable attack on its “struggle heritage”. The case against Malema was vigorously contested by the ANC, as an intervening party, in court.

The internal disciplinary charges the ANC pressed against Malema - which coincidentally more-or-less ran parallel to this case - stemmed from his refusal to submit to internal party discipline and various other inflammatory remarks he made. But they did not relate to his singing of this song.

The High Court ruling that the relevant words of the song did indeed constitute hate speech was also appealed by both Malema and the ANC, and the ANC persisted with its appeal well after Malema’s expulsion. It was shortly before the appeal was due to be heard in the Supreme Court of Appeal in late 2012 that AfriForum reached a mediated settlement with both the ANC and Malema. The parties agreed that whatever its place in the past the song would not be sung in the future.

It was Malema and the EFF’s partial breaching of this agreement – usually involving switching the word “kill” with “kiss” in their chants – that led AfriForum to recently go back to court. This time the case was heard by a judge who came from the liberation movement tradition (he had served as an ANC mayor in the mid-1990s) who ruled there was nothing hateful about this song after all.

Dangerous rhetoric, reckless reporting

There is very little then in the New York Times or Washington Post’s commentary and reporting on this issue that can be relied upon. These publications also have a long track record of publishing, and then stubbornly failing to correct, provable falsehoods on this issue.

Malema, quite famously, says what he means, and means what he says. Sooner or later this kind of rhetoric gets people killed, in one way or another, if only by the shattering effect it has on fundamental moral taboos. When political leaders endorse killing it clearly has a demoralising effect across society. As Machiavelli noted, quoting Lorenzo de’ Medici, “The example of the prince is followed by the masses, who keep their eyes always turned upon their chief.” The ultimate victims may, moreover, not always be the desired or intended ones. It could be a helpless old pensioner attacked in his home by robbers, or the girlfriend of a jealous man, or the criminal captured by an enraged mob.

Though Malema and many of his fellow travellers in the West may openly fantasise about a violent racial reckoning with the white minority in South Africa, it is foreign immigrants who are as - if not more - likely to be victimised in such a pogrom, should it ever be successfully summoned into existence.

While the EFF is currently not in national government now, it could well be after next year’s elections. If the ANC receives less than 50% of the vote nationally next year - or in key provinces like Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal – it will need to find a coalition partner if it is to continue government. The offer Malema will bring to the table is the opportunity for fellow radicals inside the ANC to throw caution to the wind and finally bring the national revolution to its culmination in a festival of racial looting and destruction.

The more important question relates to the constraints upon such a racialist agenda being realised. As the historian C Vann Woodward wrote of the rise of Jim Crow in the American South, “the South’s adoption of extreme racism was due not so much to a conversion as it was to a relaxation of the opposition. All the elements of fear, jealousy, proscription, hatred, and fanaticism had long been present, as they are present in various degrees of intensity in any society.”

Following Woodward, what will enable them to return to dominance in South Africa as well, will be the weakening of the restraining forces that have “hitherto kept them in check”. One of the great restraining forces is, as it was in the American South, the influence of Western liberal opinion.

Malema may not care what the New York Times or Washington Post says on the matter, either way, but there is a huge swathe of the intelligentsia in South Africa that unquestioningly follows the moral and intellectual lead of liberal America. This includes journalists, academics, human rights lawyers, many politicians, government officials, and so on. The failure by elite Western opinion to clearly condemn Malema’s murderous chants and death threats has the very real effect of disabling this potentially countervailing opinion within South Africa.

The “line” being laid down in publications like the New York Times - that there is nothing concerning or to be said here - is thus not just false and misleading but morally reckless as well.

Footnote:

[1] The complications in calculating an accurate farm murder rate, which the Washington Post fails to grapple with, are these: (a.) The definition of a farm applies to farms and smallholdings where agricultural activity occurs. However, these may not necessarily be covered by the agricultural census, which counts VAT registered entities only. (b.) The victims of farm murders are predominantly farmers and their immediate family members. But ordinary workers can be caught up in these attacks and killed as well. According to an analysis of 2 250 farm murder victims recorded between 1990 and 2023 by TAU SA, an agricultural union, 63,6% victims were farmers, 25,5% their immediate family members, and 9,5% were workers. 85,5% of these victims were white. Anecdotally, coloured and Indian commercial farmers, though relatively few in number compared to white commercial farmers, have also been a target of farm murders, especially in KwaZulu-Natal. (c.) The official definition of farm attacks excludes “Cases related to domestic violence or liquor abuse, or resulting from commonplace social interaction between people are excluded from the definition.” Murders related to inter-personal violence - which account for the great bulk of murders (and of the murder rate) nationally - are thus not included in the SAPS farm attack statistics.

Here are the problems with this argument:

(1)There are no compelling evidence that even during the armed struggled these songs led to attacks on farmers. We can speculate as to why, but even when aimed at liberation activists and armed members, it did not lead to farm attacks. So here the historical context doesn't seem to be particularly helpful for your argument and loses the wood for the trees. Would ordinary South Africans in a post-Apartheid dispensation be more susceptible? Again we can only speculate...

(2) There is not good enough data on farms, rural areas and farm murders. This and many others discourses would greatly benefit from better data. Your own data and sources have been rightly criticized. There is a lot of speculation and a lot of fitting the data to the narrative on all sides. (If we say look at income, would we conclude there is a black genocide in South Africa based on class as a metric / the WC government allowing coloured / black South Africans to die on the Cape Flats - again all of it silly, yet farm attacks seem to be not much different reasoning with race and murder rate seemingly being used as the argument). Farming - again the data here is problematic (The Conversation had a good article on this recently) - is still overwhelmingly white. There is no evidence, despite the horrific levels of violence / torture in some of these attacks (part of some explanation / but not strong enough on its own), that it is driven by racial hatred or more specifically inspired by the song. (For instance isolation and potential law-enforcement / public response is legitimate explanation. I would for instance like to see statistics on all rural violent crime and specifically where it is not in close proximity to communities / people living close to one another)

(3) The latest court ruling can be argued and we will have to see the outcome of the Afriforum appeal. Mistakes were arguably made by Afriforum and potentially the judge (ruling that in all context the song is not hate speech). But the point is, we have legislation and a legal process to test competing claims and arguments about the song and what it implies in a specific context. Again, this is the test for the courts under the specific legislation - your argument should focus on this aspect if it wants to criticise the specific case. The liberal thing, is surely to let this play out and then respond accordingly?

Finally, it is striking how many of the arguments made against the song (including in this piece), can be made on even better grounds against the Apartheid Flag. Yet many that want the song banned, don't think the flag should be banned. Yet, our highest court, has not banned the flag, but prescribed when its use would not constitute hate speech.

Two things follow from this, how inconsistent our classic liberal / reactionary right (best way to describe PW and IRR these days) have become and how they are really no different from the left. PW and the IRR, used to be much more measured, but today seem to be prone to all the same identity politics, ideological bias and culture war politics (our local version). That actually, things are still pretty liberal in South Africa after all...I don't think the song is healthy or should be encouraged, but I do think our political system is handling it the best it can, according to the constitution and on pretty liberal grounds - whilst the political actors and space seem to do there thing as well...All very liberal - right?

The only reason why liberal media attacked Musk is because they're looking for any reason to do so after he favoured conservatives with Twitter. They don't give a damn about South Africa.